A 21-year-old female dancer presents to the clinic with neck pain

following a strenuous rehearsal. Physical examination reveals a decrease

in cervical flexion, and a palpable subluxation present at C3-C4 on the

left.

SAMPLE CASE

A 21-year-old female dancer presents to the clinic with neck pain following a strenuous rehearsal. Physical examination reveals a decrease in cervical flexion, and a palpable subluxation present at C3-C4 on the left.

|

|

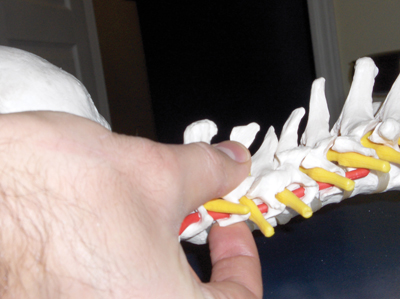

| Picture 1: Displayed are the contacts for an Anterior Cervical Subluxation. Note the index finger on the anterior aspect of the TVP and the thumb pad on the lateral aspect of the spinous process of the involved segment. Advertisement

|

The remaining patient history, X-ray analysis and neurological testing are unremarkable. The doctor has undergone basic Thompson Technique training in school, and Thompson analysis reveals a short left leg in the extended position. The doctor instructs the patient to turn her head to the left, which produces no change to the leg lengths. The doctor then instructs the patient to turn her head to the right, which results in balanced leg lengths. Right head turning producing balanced legs indicates a Right Cervical Syndrome with the problem located on the opposite side. The doctor then palpates along the lamina pedicle junction on the patient’s left side. A tender nodule is present at C3. The doctor takes his/her contact at the site of the nodule and thrusts P-A, in line with the disc and perpendicular to the facet, which is the standard protocol for a Classic Cervical Syndrome. However, over the next few treatments, the doctor continues to find the same cervical subluxation occurring. Also, the patient now complains that her symptoms are getting worse with each treatment.

A patient complaining that she is getting worse with each treatment should be a warning sign to all doctors that they are missing the problem. This case is a typical scenario of an Anterior Cervical Subluxation pattern.

If a doctor is unaware of this subluxation pattern, and is unaware of how to detect and correct the subluxation, he/she can produce further damage to the patient. In this edition of Technique Toolbox, I will discuss how to detect and correct an Anterior Cervical Subluxation (ACS) and how it differs from a Classic Cervical Syndrome subluxation.

BUT FIRST, SOME HISTORY

The Thompson Technique was created by Dr. J. Clay Thompson in the early 1950s. Dr. Thompson was a mechanical engineer before becoming a chiropractor, and was the head of the Palmer Research Institute for 10 years. Using his background in mechanics, Clay utilized Newton’s first law of physics, the Law of Inertia, to develop a system of adjusting by using a table that incorporated a drop-piece mechanism. The drop-piece created less strain on the patient while performing adjustments. Clay developed the Thompson Technique as a full spine approach to detect and correct subluxations, and utilized leg length analysis, palpation and X-ray findings as primary diagnostic measures. Although Clay’s work was revolutionary in his time, Clay was limited by the science of his era, and thus, certain gaps existed in the technique. This is not meant to discount the tremendous work that Clay developed, but only to recognize, that no matter how great an individual’s work is, there are always strengths and limitations to it. The way to constantly improve the technique is to recognize any limitations that may exist, and strengthen them. The technique for detecting and correcting an ACS, is one such example.

The ACS is considered a part of the cervical syndrome category. However, the biomechanics of this cervical syndrome are completely different than they are in any other cervical subluxations.

So, how do we detect and correct this subluxation pattern?

Step One: Analysis:

- Prone leg length analysis reveals a contracted leg in extension.

- Doctor instructs patient to rotate the head to the left and then to the right.

- In our sample case, head rotation to the right balances the patient’s legs, thus, a Right Cervical Syndrome is present, but the affected side is contralateral to head rotation.

- Doctor palpates the cervical spine’s facets on the left side, and reveals that a tender pea-shaped nodule is present. (This nodule represents an inflamed facet capsule, and usually indicates that the vertebra has subluxated posterior with spinous rotation away from the nodule side.)

- Doctor corrects the cervical subluxation with a Classic Cervical Syndrome adjustment. (Contacting the nodule found on the facet, and thrusting P-A.)

- However, the patient now complains that her symptoms are becoming worse with each treatment.

- This is a big indication that the doctor is missing the problem. Once a patient complains that they are getting worse with each treatment, the doctor must rule out a possible Anterior Cervical Subluxation.

|

|

| Picture 2: The Anterior Cervical Subluxation contacts are displayed on a patient. Note that the head rotation is to the ipsilateral side of the contact. |

(I am often asked why would the doctor not just rule out ACS initially, before beginning to adjust for a Classic Cervical Syndrome? This is a great question, and is the very reason I am using this case as a sample. To date, most doctors who have taken a basic course on Thompson Technique in Chiropractic College may not have learned about the ACS and how to rule it out in the initial assessment of their patient. This is because it is viewed as advanced information and is not usually incorporated into undergraduate training. For already licensed DCs, skills for dealing with ACS can be acquired as continuing education. This case study, then, is meant to expand on traditional Thompson Technique knowledge – which many DCs are currently trained to employ – and take the doctor to the next step when a patient is observed to not improve with adjustments for Classic Cervical Syndrome. In time, up-to-date and comprehensive training in the Thompson Technique will result in optimal assessment and treatment of the patient from the initial visit.)

Step 2: Criteria for an Anterior Cervical

When an ACS is suspected, there are three criteria that are required to confirm a doctor’s suspicion.

- Cervical Syndrome nodule is present.

- Ipsilateral posterior cervical muscular concavity or flaccidity is present on the nodule side.

- A-P cervical x-ray or palpation reveals spinous deviation toward the side of the nodule.

SUBLUXATION BIOMECHANICS

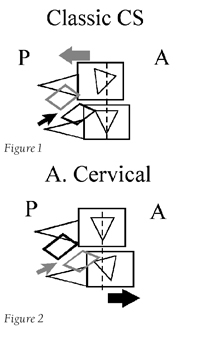

In an ACS, the cervical vertebrae subluxates anterior, with spinous rotation toward the nodule side. This is the exact opposite of the Classic Cervical Syndrome, which explains why the patient’s symptoms become worse with initial treatment. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

|

|

Note in both Figures 1 and 2 that the Classic Cervical Syndrome subluxates posterior with slight spinous rotation away from the nodule (thick grey arrow). The Anterior Cervical subluxates anterior and has a greater rotational component with spinous deviation toward the nodule (thick black arrow). Also note that the nodule occurs at the same facet location. However, with the Classic Cervical Syndrome, the superior vertebrae subluxates and causes the facet to stretch through the segment’s inferior articular facet (thin black arrow). In an ACS, the inferior vertebrae subluxates producing the stretch on the facet capsule through the segment’s superior articular facet (thin grey arrow).

Step 3 Correction: Anterior Cervical Adjustment: (See Pictures 1 and 2)

- Patient: Prone.

- Doctor: On the involved side, head of table.

- Table: Cervical piece in the ready position, dorsal piece inclined.

- Contact: PIP of index finger on the anterior aspect of affected TVP, and tip of the thumb on the lateral aspect of the spinous process (on the involved side).

- Stabilization: Opposite zygomatic arch or parietal bone.

- LOC: A-P with rotation.

In this adjustment the thumb contact on the lateral aspect of the spinous process is critical with respect to the correction of the rotational aspect of this subluxation pattern, whereas, the index finger contact on the anterior aspect of the TVP, corrects for the anteriority.

It is important to note that the doctor cannot change the contact to the posterior aspect of the opposite transverse process. The doctor must always be cognitive of the biomechanics involved with the subluxation:

- The opposite transverse process is not subluxated posterior, it is in its neutral position.

- It is only posterior relative to the subluxated anterior transverse process on the affected side.

- If the opposite traverse process is contacted, the doctor will move the entire complex anterior, and thus cause a greater problem.

It is imperative for us to understand all potential subluxations involved with an issue. If we don’t expand our knowledge base to learn modifications and inclusions to a particular technique, we risk potentially harming a patient. The Anterior Cervical Subluxation is a perfect example of this. If a chiropractor only learned basic Thompson Technique, they would not know this procedure, and potentially miss the primary problem.

As usual, I have only scratched the surface of the Thompson Technique. If you would like to learn more, please visit www.ThompsonChiropracticTechnique.com. If you have any comments, please contact me at johnminardi@hotmail.com.

Until next time . . . Adjust with Confidence!

Dr. John Minardi is a 2001 graduate of Canadian Memorial Chiropractic

College. A Thompson-certified practitioner and instructor, he is the

creator of the Thompson Technique Seminar Series and author of The

Complete Thompson Textbook – Minardi Integrated Systems. In addition to

his busy lecture schedule, Dr. Minardi operates a successful private

practice in Oakville, Ontario. E-mail johnminardi@hotmail.com, or visit www.ThompsonChiropracticTechnique.com

Print this page