Evidence-based Guidelines – A Double-edged Sword

By Dr. John Triano DC PhD

Features Clinical TechniquesDeveloping an understanding for the role of evidence-based practice in chiropractic.

One is hard pressed to think of a phenomenon that has spread as rapidly throughout the international system of health delivery as evidence-based care. Even the, now obvious, concept of scrubbing a surgeon’s hands between working in the cadaver lab and at the surgical table took longer to become accepted as standard of practice.1 Over the past 10 years, the ideas led by Sackett and colleagues from McMaster University2,3 merged with those of Archie Cochrane of Great Britain to foster a demand for improving the quality and cost of care through implementation of guidelines. Now, approximately 32 years after Sackett and Haynes first expressed their views on how to improve their clinical decision making, evidence-based practice has become an increasing focus within health-care education, policy making and practice benchmarks.

Frequently, however, there are one or more mismatches between the understanding of evidence and its implementation. The differences are often driven by disparities in the motives behind what is presented as “evidence” and in the implementation of the resulting judgments. Being “evidence-based” was never intended to be “evidence-enchained”. Indeed, the concepts of evidence-based practice and those of guideline development, while sharing some common interests, are inherently incompatible when there is an attempt to directly overlay them to create a template for patient care.

Frequently, however, there are one or more mismatches between the understanding of evidence and its implementation. The differences are often driven by disparities in the motives behind what is presented as “evidence” and in the implementation of the resulting judgments. Being “evidence-based” was never intended to be “evidence-enchained”. Indeed, the concepts of evidence-based practice and those of guideline development, while sharing some common interests, are inherently incompatible when there is an attempt to directly overlay them to create a template for patient care.

The underlying motivation and value of evidence-based practice is in the guidance of clinical decision making for individual patients considering the context of that individual.3 The elements of that context include 1) the complexity of their condition and circumstances, 2) the best available evidence on what has been shown to be effective for most cases, 3) the provider’s expertise and experience, and 4) the patient’s preferences and beliefs. Regulatory, or evidence-based policy making, on the other hand, has as its primary motivation the management and distribution of health-care resources to the population as a whole. The distinctly different focus between the needs of the individual and those for the conservation of social resources commonly places the provider in real conflict while engaged in the doctor-patient intervention. A satisfactory ethical conclusion of that intervention is reliant upon the conduct of common good-faith effort and intent in the exercise of patient-centred duties by both the provider and the administrators of the health-care system under which he/she practises. Failure of either party results in, at least, moral if not tangible harm to the primary stakeholder, the patient.

An evidence-based focus carries both advantages and disadvantages. There are failings to its blind implementation in a similar way that blind application of treatment that is independent of patient need may be problematic. As identified by Haynes, Devereaux and Guyatt4 in their revised understanding of evidence-based clinical decision making, clinical expertise is an evolving state. It is, by nature, the combined knowledge of the clinical circumstance, patient preference and actions and the research evidence that exists that may influence outcome. And this, in turn, will influence the evidence that is available for practitioners.

So, what are the advantages of an evidence-based, patient-centric approach to health-care delivery?

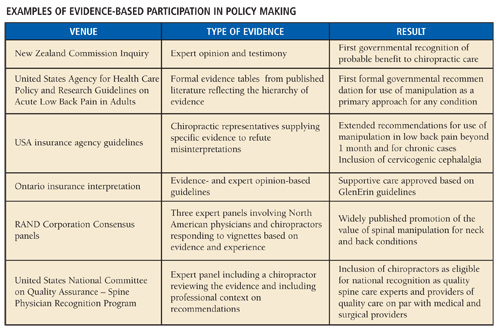

Policy-makers are the designated social arbiters determining access to and compensation for services. The rapid adoption, internationally, of the expectation for positive benefits from regulatory, evidence-based policy making is a reality. The goals are an increased quality and reduced overall cost of care. Who can argue against such laudable goals? Membership at the table requires participation in developing, cataloguing and interpreting the evidence that is used. Moreover, participation garners the only productive means by which professional stakeholders can represent their expertise and successfully influence interpretation of the findings in a context of the patients for whom their services are beneficial.

Examples of the positive impact on policy from professional participation in review of the evidence on behalf of chiropractors are given in Table 1. Each one of the examples raised the cultural authority and professional visibility of chiropractic internationally.

At the individual level, there is advantage to both the patient and the practitioner in using evidence to guide their first efforts in helping patients, in the few cases where such evidence exists and is strong. Studies are available to show that under such circumstances, the average patient improves more quickly, suggesting higher quality care has been administered. The patient benefits clinically and the provider’s reputation benefits accordingly. Over time, this translates into a wider network of referrals both from patients and other health providers who develop greater trust in the individual doctor.

In the absence of strong evidence, or where initial efforts have failed, a reasonable course of care uses best-faith efforts based on what information exists, experience and an informed patient preference. Results are closely monitored for signs of lasting beneficial change.

If the goals of evidence-based care are so laudable, how can there be disadvantages?

If the goals of evidence-based care are so laudable, how can there be disadvantages?

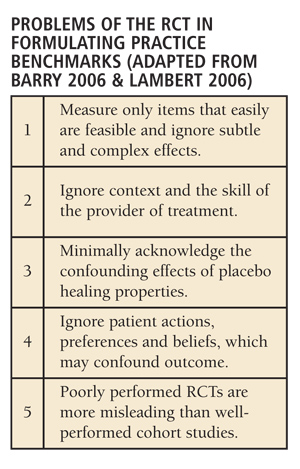

Clearly, one example is the case where evidence is lacking or is inappropriate for the patient whose plan of care is being considered. Lambert2 has defined the problems of trying to apply population-derived evidence to individual patients. Many clinicians, epidemiologists, medical sociologists and statisticians agree that evidence derived from randomized controlled trials, and other studies on the effects of treatment, cannot be applied directly to the management of individual cases. Even in circumstances where there is a “fit” between the evidence and a particular case, based on the very nature of statistical analysis underpinning these papers, it can only apply to those who represent the average behaviour. That leaves about half of the population whose response to that care can be expected to deviate from the norm, increasingly, as they move further from being a close “fit”.

The pre-eminence of the randomized clinical trial (RCT), generally a positive factor for population health questions when high-quality RCTs exist, can be a significant negative compass that actually misguides care decisions. Unquestion-

ably, the concept of providing care that has been proven to work is sensible and morally correct.5 The problem is that the complexity of conducting a randomized trial, with its inherent methodology issues, is not only daunting but often unrecognized by those who have never tried to conduct one. Furthermore, since it may be conducted utilizing a sample of patients of whom the individual is not a good representative, the RCT tool often measures the wrong things, with respect to the individual patient.5 The works of Barry5 and Lambert2 succinctly describe the various mismatches (Table 2) that may arise between results from an RCT and the contextual elements for an individual patient.

In contrast to RCTs are the methods of cohort (non-randomized) and qualitative studies that arguably are more suited to the study of complex and multicomponent treatments. Ironically, while the acceptance of these tools has increased, a simultaneous emphasis on criteria judging methods that yield acceptable evidence has not kept pace. If study methods are designed to meet evidence criteria, the results are often superficial and lack originality.2 Other efforts are often deemed insufficient to alter clinical practice recommendations regardless of findings 6.

Finally, the methods of evidence summary (e.g., meta-analysis, systematic literature synthesis and evidence rating) hardly are infallible and are prone to the same types of bias that exist in original papers7;8. Little attention is given by policy makers to the context of how the summary was framed, what question was asked and how consistent were the ratings applied to original works that were included. Indeed, in the warnings of prominent proponents, evidence-based care is “perpetuated by the arrogant to serve cost cutters and suppress clinical freedom”9. While evidence-based care offers a much-needed critique of health-care delivery, it is susceptible to manipulation6:10.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there are common failings between the proponents and the opponents of evidence-based care. The weaknesses revolve primarily around the perceptions of trust and good-faith efforts. As discussed immediately above, there is no question that manipulation of good science can be accomplished a number of ways to yield conclusions and recommendations that are to the user’s end. Despite the oft-quoted common wisdom among proponents of evidence-based care that higher quality and lower costs will result, there remains little evidence that there is an overall benefit to patient outcomes2. When, and under what conditions, benefits are seen is largely unknown.

At the same time, practices beyond the bounds of patient-centred care manipulate the system for short-term monetary benefits. Whether qualitative or quantitative research methods are used to study practice patterns, the valuable clinical benefits of an effective treatment, administered based on tradition or preference rather than clinical need, will be diluted and appear ineffective.

The problem of bias against particular treatments

The experience of practising under health-care systems that highly value regulatory, evidence-based policy does not adequately consider the problem of bias against certain treatments or the impact of misdiagnosis resulting in inappropriate care.

Bias against treatments arises in both systematic and individual forms. The methodology problems associated with studying complex or multiple-component treatments – e.g., manipulation plus exercise versus multiple forms of manipulation versus sham/placebo manipulation – make it more difficult to reach high-quality ratings when these are compared to typical evidence-based criteria2. Simpler comparisons like those of contrasting a single drug to placebo are favoured since the RCT tool is better equipped to evaluate them. Individual bias is shown when providers fail to recommend treatments less preferred despite the evidence. With similar effect, misdiagnosis, based on the absence of skilled assessment relative to the treatment, leads to applying ineffective treatment. Once in a diagnostic stream, therefore, patients do not commonly have the opportunity, within the system of health care, to seek alternative treatment.

Who is to decide what the motives are?

The educational institutions have multiple roles in these debates. First, in the mission to provide quality education to graduates, the institutions must equip doctors to manage and minimize the inherent conflict within the doctor-patient interaction caused by the social demand to be “evidence-based.” The core of a solution for this dilemma is provided in Sackett’s original thesis on evidence-based practice. The institutional mission must be to equip the provider to integrate all four elements of the context within which a patient presents and to formulate a treatment or management plan that a) uses methods for which there is good evidence where it exists as the FIRST effort to resolve the clinical problem, b) to benchmark outcomes based on realistic expectations and c) to anticipate the next steps in a prospective staged management plan, should the first effort fail, taking into consideration those methods where there is some evidence or clinical expertise that the result is likely to be beneficial.

Educational institutions, in their broader mission to contribute to the health of society, must not permit an atmosphere that encourages being “evidence-enchained”, binding intellectual integrity and creativity. Through a mission to generate new knowledge, research must move forward to address questions critical to the advancement of patient care. Serving as a venue for inquiry and open intellectual dialogue, institutions must accelerate investigation and debate over ideas and methods of care, for which there may not be current evidence, must be fostered and accelerated. Successful execution requires the building of mutually respectful, intraprofessional partnerships with practitioners and associations as well as interdisciplinary partnerships with other institutions and agencies. The key to bountiful achievement is for all partners to remain focused on the principal patient-centred issues, providing expertise and resources while avoiding the common pitfalls of inner-circle arrogance and hubris.

Evidence-based care is an evolving, but well-entrenched, concept. It is truly a double-edged sword fraught with challenges. As professionals and stake-holders of the system of health care, we have the obligation to meet social expectations to demonstrate the evidence for quality from our services. We have the opportunity, as trusted members of the health-care team, to exercise our voice through the compilation of relevant evidence and to influence the future for us all.

While the relative value of services is ultimately set by a free society through the long-term balance of supply and demand, the profession and its institutions, together, must learn to be bilingual. With one voice, we must develop the ability to speak within the constituency of chiropractors: acknowledging our heritage and its contributions as well as performing dispassionate but lively debate over its elements. We must identify those elements that give force to patient value versus ideas that were sincere, but misguided. With the other voice, we must translate what is known to add value to the health-care system and its broader stakeholders in terms that are meaningful to them. As members of the trusted health-care team, some of the compelling questions we face today include:

I. What are the mechanisms of care that is administered?

II. How do we harness those mechanisms to improve patient outcomes?

III. Who are the best candidates for care that we provide?

IV. How much care is needed to meet outcomes society values?

V. What are the tangible benefits to the patient and to society from greater inclusion and access to our care in terms of

• Reduced waiting times?

• Reduced suffering?

• Improved functioning?

• Improved quality of life?

• Enhanced value to the system of health-care delivery?

While evidence-based care and guidelines can be a double edged-sword, let us not allow it to be a Sword of Damocles that only hangs over our heads, let us strive to take advantage of the other edge. Until then, instead of influencing the interpretation of evidence in the context of our clinical expertise, we speak only to ourselves.•

Print this page