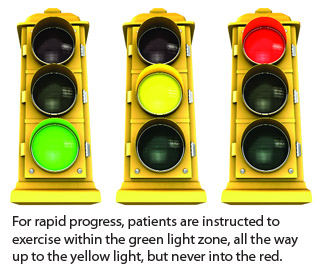

The red light, green light analogy for patient instruction

I want to have my patient start some exercises, but I’m afraid they might cause more pain and make the patient upset with me.”

I want to have my patient start some exercises, but I’m afraid they might cause more pain and make the patient upset with me.”

This concern is very common and understandable. As chiropractors, we work hard to help our patients feel better, so the last thing we want to do is recommend exercises that cause more pain. To avoid this, I have found one of the best methods is to give very clear instructions when the patient first begins exercising. I find it necessary to communicate two topics in particular: what the patient can expect to feel, and how they can tell if they have pushed the exercise too far. This is important for patients who have never exercised before and don’t know what to anticipate. It’s also necessary for athletes and weekend warriors who tend to move along too quickly. All patients need clear, specific guidelines when starting an exercise program.

WHAT TO ANTICIPATE

I find that most patients have little experience in specific exercising; except for the occasional recreational pursuit, many patients have never done any exercises before. These patients will do a lot better when they know exactly what they can anticipate feeling as they begin performing the exercises. They appreciate the guidance and reassurance, and are more likely to follow through with my recommendations.

I tell them the following: “You are likely to feel some soreness, some stiffness, perhaps even some mild irritation in the involved joints and muscles as you begin to exercise this area. That’s to be expected, and it means we’re working in the right area.” This prepares patients for the soreness from starting to exercise a problem region, and provides some encouragement. Then I discuss the possibility that they will feel some actual pain. It’s important to differentiate soreness and stiffness from true pain.

PAIN-FREE RANGE OF MOTION

When I start an exercise, I want my patients to do it so it doesn’t cause pain because I don’t want them to continually aggravate the area that is healing. Some people (athletes in particular) think that an exercise has to be painful to be beneficial (the “no pain, no gain” concept). I very directly tell my patients that I don’t want them exercising through or beyond a painful point. While this seems obvious to most of us and to many patients, it’s critical to cover the topic of pain when exercising. Otherwise, our patients won’t know when they have done too much. With some patients, I find it necessary to explain the concept of overflow of training.

OVERFLOW

Overflow is a neurological concept that has been noted frequently when studying strength gains. In fact, scientists have been able to measure the benefit of overflow rather accurately. Strengthening extends beyond the range we’re exercising whenever we exercise in a limited range of motion. This amount is around 15 degrees beyond the exercised range in most types of exercise. Isometric exercise provides only a limited benefit (around five degrees) – one reason why I seldom use isometric exercising.

The great news is that the 15-degree overflow of stimulus eventually expands the pain-free range. That range gradually but inevitably gets bigger and bigger when a patient exercises regularly in the pain-free range. This allows a more steady response than when the patient tries to force an expansion in range and develops a return of painful movement. The only problem is communicating this accurately.

RED LIGHT, GREEN LIGHT

I have found that most patients will nod their heads in understanding when I say “pain-free range,” but not really comprehend what I want them to do. This is because the words sound familiar, but they are not really sure how to implement this in their exercising. I use a common analogy for this concept to ensure accurate communication.

I tell my patients to expect some soreness and stiffness, but to pay attention if their bodies give them a pain message while they’re exercising. I explain to patients that the pain message is a warning signal, similar to a yellow traffic light. It doesn’t mean they have hurt themselves yet, but if they push the exercise beyond this point – to the red light – they risk aggravating their condition and slowing their progress. I say to patients, “I want you to do the exercise all the way through the green light and up to the yellow light. I do not want you to exercise to the red light. That is unnecessary and likely to slow your progress, rather than speed it up.”

An example of this is in shoulder exercises. It’s easy for a patient to start exercising and want to push beyond the pain to try and make quicker progress. With chronic conditions and after accidents, strengthening the shoulder flexors is often necessary. If the patient pays close attention, an obvious painful point of restriction (yellow light) can usually be identified. As long as the patient continues to do the exercise repetitively to the yellow light and not beyond to the red light, rapid progress can be expected, and the green light area will increase.

The increase in the green light area is not always steady or linear. Sometimes patients will notice the green light area is smaller than the day before, even though they have been gradually improving. Some patients will force the shoulder to exercise beyond that day’s pain point because they don’t want to lose the progress made. This second-guessing must be avoided. We may not know the reason for the temporary loss of pain-free motion, but we know that forcing beyond is not the answer. For whatever reason (weather changes, increased activities, or “star alignment”) the body is letting us know that it cannot tolerate as much stress to the area as before. One of the most important lessons patients can learn in our offices is to listen to and trust the wisdom of their bodies.

Don’t be afraid to start your patients on an exercise program when they still have pain. Waiting will just drag out the treatment program and make their recovery more difficult. First, reassure your patients by telling them what to anticipate. Then give them clear instructions using the red light, green light analogy to encourage them to start and continue with the exercises. This also prevents patients from pushing the exercises too far, too soon. They will be comfortable with the soreness and stiffness from a new exercise program, but they will understand that a pain message is something they should not ignore.

When exercises are integrated into the early phase of chiropractic care, patients make rapid progress. The red light, green light model helps keep that progress steady, with few exacerbations. The end result will be more consistent chiropractic results, and patients who appreciate your expertise in the field of musculoskeletal problems.•

Print this page