How are you feeling Mr. Harrison? Does your back feel better today?” While we may ask our patients these questions each time they visit

How are you feeling Mr. Harrison? Does your back feel better today?” While we may ask our patients these questions each time they visit, the answers we receive may vary depending on any number of daily factors that affect a person’s state of mind. Measuring pain has always been a subjective process with a high degree of variability. Understanding how patients perceive their pain and how that pain affects their daily life helps a practitioner determine an appropriate treatment plan. Documenting patient progress through pain and functionality scales allows a practitioner to re-evaluate and modify treatment plans in order to obtain optimal clinical outcomes.

Low back pain

Low back pain (LBP) affects between 67 per cent and 84 per cent of people in industrialized countries during their lifetime. It is the fifth most common symptom for which patients visit physicians, with approximately one quarter of adults reporting LBP lasting at least one day in the past three months. One out of every four acute low back pain patients will have a recurrence within one year and approximately 10 per cent will go on to develop chronic LBP. LBP is known to limit activities of daily living and is the single most costly medical condition responsible for lost workdays and disability claims.

Acute low back pain is generally severe. Often, activities are reduced or avoided because of concern the activity will increase the pain or cause further injury. Furthermore, performing normal daily tasks can be difficult due to the limited range of spinal movement or due to the pain itself. People with acute back pain are often unable to work, and even if they can work, they may be less productive. The pain may be so severe that it can interfere with sleep, resulting in periods of fatigue. Pain may also interfere with social roles and functioning; some activities may need to be avoided altogether.

Chronic low back pain is usually described as deep, aching, dull or burning pain in the area of the low back or travelling down the legs, and lasts longer than three months. Pain is worse while sitting too long in one position, driving, spending long periods bending over, lifting, bending or pulling (or doing physically demanding work), and when not exercising regularly.

The functional limitations associated with acute and chronic low back pain are similar. For example, moderate pain or discomfort and some fatigue are experienced, as well as difficulties lifting objects and moving about. The emotional state is often affected, in part due to the frustration that results from living with constant pain. Depression is also common in individuals with chronic pain. In addition, the pain may affect the capacity to sustain social relationships due to avoidance of certain activities.

How do we measure pain?

There are a number of measures available to assess pain, each with their strengths and weaknesses. While many pain assessments are used primarily in research settings, a number of surveys may be appropriate and useful in a clinical setting.

Pain surveys can be as simple as assessing the intensity of pain on a scale from zero to 10, such as the Numeric Rating Scale, or as complex and multi-dimensional as assessing the intensity, quality and functional implications of the pain, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire. These surveys ask more detailed questions, including any limitation low back pain has on a person’s daily activities and general function.

Are pain measurements useful?

Simple scales such as the VAS and NRS are one-dimensional, and while they allow for a quantification of current pain level, they do not address any qualitative or functional implications of pain. Intensity level alone does not determine how pain affects a person’s quality of life. Some individuals may rank their pain as low but may not be able to easily climb the stairs or perform other activities of daily living (ADL). Others may rank their pain as high but are able to perform ADL at a relatively normal level. Therefore, in order for a pain survey to be useful to the practitioner, it needs to allow for a multi-dimensional assessment of low back pain.

How do I incorporate pain measurements into my practice?

Pain assessment is normally performed during the initial consultation with a patient. It can thereafter be incorporated on weekly re-assessments. In order to seamlessly incorporate pain surveys into a clinical setting, it is helpful to address the following criteria:

- Is it easy to administer by practitioner?

- Is it easy to complete by patient?

- Does it provide a quantitative score value?

- Does it provide functional implications of pain on activities of daily living?

At the Meditech Laser Rehabilitation Centre, we have incorporated the Brief Pain Inventory into our assessment and re-assessment process. Documenting the progress of our back patients provides a rationale for changing treatment parameters when applying low intensity laser therapy. Parameters such as duration, power output, pulsing frequency and duty cycle can be increased systematically depending on the patient’s response to treatment.

Case study

A 54-year-old bus driver who has been driving a TTC bus for 31 years has a long history of low back pain with many disruptions of work and periods of being on light duty. In January of this year, he returned to driving and was doing well until recently, when he lifted a ramp. He now has acute low back pain with radiation of pain to both lower extremities accompanied by numbness. He has been on physiotherapy, analgesics, anti-inflammatories and traction without any significant benefit.

Physical examination:

- The patient appears to be in significant distress.

- He is unable to sit or lie on his back.

- Examination of the lumbar spine reveals a scoliosis with the lumbar apex to the left and acute tenderness from L3-S1.

- There is flattening of the lumbar lordosis and significant muscle spasm in the area.

Diagnosis: Disc herniation L4-5 with bilateral nerve root compression

|

|

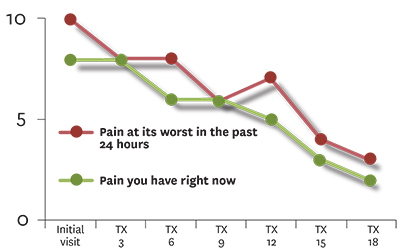

| Figure 1A: Pain at its worst in the past 24 hours and pain right now |

|

|

|

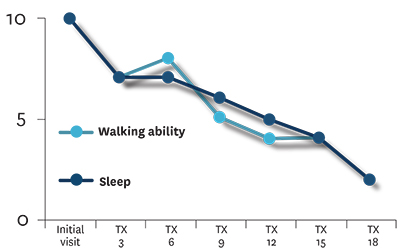

| Figure 1B: Walking ability and sleep | |

|

|

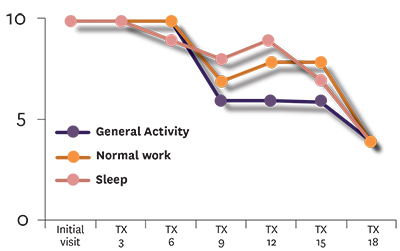

| Figure 1C: General activity, normal work and enjoyment of life |

Discussion: The patient received 18 laser therapy treatments over the course of one month. Parameter changes such as pulse frequency and duty cycle were changed every three to four treatments following re-assessment of the patient. As seen in Figure 1A, the patient’s pain level steadily decreased from a level of between eight and 10 out of 10 down to two to three. Pain interfering with sleep and walking ability also steadily decreased from a 10 down to two (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the effect of pain on general activity, normal work and quality of life stayed at a constant level of between nine and 10 for the first six treatments despite the fact the pain levels were reported as reduced (Figure 1C). These category levels did diminish throughout the treatment program, but had much greater variability and showed a step-wise decrease in value at certain time points such as the sixth and 15th treatment.

What other tests can I use to document patient progress?

While pain scales may provide some insight on how pain is affecting a patient’s activities of daily living, there are additional condition-specific surveys available that delve deeper into the implications. For back pain, the Oswestry Disability Index and the Roland-Morris Survey have been used extensively for research purposes. In part 2 of this article, we will examine the usefulness and practicality of incorporating condition-specific low back pain surveys into the documentation process of patient progress.

Systematically documenting patient progress through pain surveys allows for a more detailed examination of how a patient is responding to a current line of treatment. When dealing with low back pain, functional implications of pain on activities of daily living are particularly important and may alter the parameters of treatment such as in the case of laser therapy.

|

|

|

|

|

Dr. Fred Kahn is president and CEO of Meditech Laser Rehabilitation Centre and Meditech International Inc. Reach him at fkmd@bioflexlaser.com.

Dr. David Kunashko has lectured extensively for several colleges including the CMCC. Reach him at david@bioflexlaser.com.

Dr. Fernanda Saraga is director of clinical research and education at Meditech Laser Rehabilitation Centre. Contact: fernanda@bioflexlaser.com.

Print this page