Toronto chiropractor describes the world’s fastest-growing sport.

The ancient ritual of dragon boat racing that originated in China is rapidly attracting attention in North America and worldwide. With this recent surge in popularity, dragon boat regattas now attract a wide range of recreational and competitive teams representing clubs, communities, corporations and banking institutions, as well as nations.

The ancient ritual of dragon boat racing that originated in China is rapidly attracting attention in North America and worldwide. With this recent surge in popularity, dragon boat regattas now attract a wide range of recreational and competitive teams representing clubs, communities, corporations and banking institutions, as well as nations.

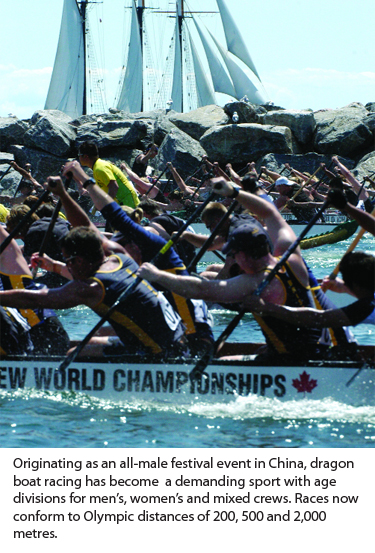

Under the umbrella of the International Dragon Boat Federation (IDBF), dragon boating has become highly organized with both Club Crew World Championships (CCWC) and World Nations Dragon Boat Racing Championships (WDBRC), each occurring every other year. Evolving from a once traditional 640-metre, all-male racing festival, the sport includes junior, premier and senior divisions with men’s, women’s and mixed crews. Race distances now conform to Olympic event distances of 200, 500 and 2,000 metres.

With men-only crews, I competed in the early days as a paddler in multiple international championships staged in Hong Kong’s renowned harbour, and later I took part in corporate dragon boat racing as coach and steersman of the Bank of Montreal’s team. Our racing successes took us to Sweden, Italy and England. In 2006, after several years of coordinating on-site chiropractic, massage and emergency services for my local club’s regatta, I was asked to be the director of health services for the Club Crew World Championships held in Toronto.

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS IN TORONTO HARBOUR

The city of Toronto created a six-lane, 500-metre world-class racing course for the 2006 world cham-pionships. Contributions from three levels of government totalling $23 million built a course that nurtures the growth of the sport and enhances the development of Toronto’s waterfront.

The task of directing health services and on-water safety necessitated dedicated teamwork and careful planning. Health services volunteers included administrators, lifeguards, paramedics, chiropractors, physiotherapists, registered massage therapists and athletic therapists. Over three days, our health-care team delivered more than 300 treatments, which were enormously well received by the athletes, thus setting a standard for other host countries. Recent chiropractic graduates Dr. Nicole Ciraolo and Dr. Scott Dunham played valuable roles as on-site director and chief safety officer, respectively. Ten sports specialty college fellows and residents formed the chiropractic contingent.

DRAGON BOAT INJURIES

While acute injuries such as cuts, abrasions and contusions were taken care of by the multidisciplinary health services professionals, most of the treatment time was allocated for common sprains and strains, performance enhancement, and muscle work between races. However, as is the case in sport, not all dragon boat injuries are common or simple.

One competitor suffering from heat exhaustion had to be transported by paramedics to the hospital.

Research shows that 25 per cent of dragon boat paddlers have at least one injury over the season that either keeps them from competing or causes them to seek professional attention.(1) When they do seek help, they are more likely to visit their chiropractor than their physician. Typically, the injuries are mainly of the sprain or strain variety (64 per cent), equally targeting the back (31 per cent) and shoulder (31 per cent) regions. The paddling stroke involves repetitive trunk flexion and rotation, followed by extension and de-rotation, as well as overhead arm abduction and flexion and then extension. At rates averaging 70 strokes per minute, this motion places extreme demands on the back and shoulder. What is referred to as “paddler’s shoulder” is usually caused by a tendinosis of the biceps or supraspinatus muscles in the paddler’s upper arm.

Injuries are associated with a longer training season, an increasing number of competitions, and more years of paddling. As the sport has become more broadly competitive, many levels of athletes train year-round. This is significant since 90 per cent of dragon boat injuries occur during training.

CALLING ALL CHIROPRACTORS

Over 2,000 competitors from more than 20 federations drawn from five continents will converge on Sydney, Australia, for the upcoming 2007 world championships where Canada is expected to have a strong showing. This country presently has approximately 50,000 dragon boaters, second per capita only to China.

Steering toward an Olympic presence, dragon boat racing is a sport that is characterized by a tremendous community involvement at its grassroots, with lots of opportunity for chiropractic involvement. The doctor of chiropractic might consider volunteering on an organizational committee, sponsoring a team, joining a crew, or providing chiropractic services at a local event. To find out why dragon boat racing has leapt ahead as the fastest-growing sport in the world, get involved. Catch the wave!•

Reference:

1. deGraauw C, Chinery L, Gringmuth R. Dragon Boat Athlete Injuries and Profiles, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 1999; 31:5. Supplement, 46th annual meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine.

‘A PAIN IN MY SIDE’

A 40-year-old female, who is a first-year, left-sided paddler with a history of breast cancer, presents with a pain in her left side that started in practice. Though steady, the pain is relieved with heat each night. She continues to train through the pain. However, two weeks later during the first few strokes of a race she feels something “give” in the lower left thoracic area. Finishing the race, she is unable to compete the rest of the day. She also experiences sharp pain with breathing, and has bony tenderness over the lower ribs. Her coach and chiropractor recommend radiographs, which are taken the next day.

Diagnosis

An undisplaced fracture of the angle of the ninth left rib

Health-care Management

1. Full medical work-up to rule out pathological fracture.

2. Approximately six weeks’ rest from aggravating activities.

3. Conservative treatment as required.

4. Graduated return to paddling.

5. Coach to review technique and efficiency of stroke.

Print this page