The 3-pronged approach: What does it mean to be an evidence-based practitioner?

By Dr. Joe Ghorayeb, DC

Features Profession Education Leadership Photo: mikolajn/Adobe stock

Photo: mikolajn/Adobe stock In recent years, a great deal of attention has been devoted to the notion of evidence-based practice (EBP) across a spectrum of fields and industries, including chiropractic. Efforts have been, and are continuously, made to identify interventions, protocols, and combinations of treatments that do or do not qualify as “evidence-based.” Differing views regarding what constitutes EBP have resulted in lively debate, prompting the World Federation of Chiropractic to release new guiding principles, reflecting how the organization views chiropractic as a contemporary global health profession.

Of these, principle #6 reads: “We promote evidence-based practice: integrating individual clinical expertise, the best available evidence from clinical research, and the values and preferences of patients.”

Many chiropractors, and the general public, would agree that the above principle requires adherence to ensure that clinicians remain up-to-date on current management protocols, use near real-time data to make care decisions with confidence, and improve transparency, accountability and value, as well as quality of care and outcomes.

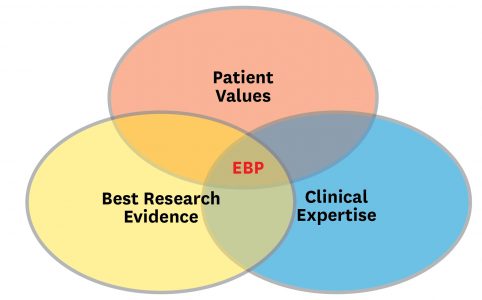

Anyone familiar with the concept of EBP recognizes the popular figure depicting an equally weighted 3-pronged approach considering best research evidence, clinical expertise and patient values in order to settle on a mutually agreed upon strategy between the clinician and their patient in an effort to administer high-quality, patient-centered care that is supported by good evidence.

But is this the approach espoused by Sackett? Considered by many to be a pioneer of evidence-based medicine (EBM).1 In his editorial, Sackett defines EBM as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”

This is to be interpreted as the clinician gathering the totality of available research evidence regarding a particular topic and applying it to the patient case, then using their expertise, not experience, in applying said evidence while working with the patient to come to an agreement about the appropriate plan of care in order to achieve the best prognostic outcome possible. Thus, the impetus behind EBM was to encourage clinicians to move away from experience-based medicine.

Sackett defines EBP as “integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” Nowhere in his paper does Sackett express equal weighting of this 3-pronged approach. Instead, he recommends that we utilize all three components to achieve positive outcomes.

Presented below is an alternative view of the aforementioned 3-pronged approach to EBP that aligns more staunchly with what Sackett was likely trying to portray.

This image on this page, of the Pillars of Creation, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, demonstrates an attempt at star formation. We can observe that these pillars are not equal. In the context of applying the 3-pronged approach of EBP in clinical practice, we may consider the tallest pillar to reflect best research evidence, the middle pillar to reflect our expertise in applying the best research evidence in clinical practice, and the shortest pillar to reflect patient values/preferences.

In considering patient values/preferences, a strong argument can also be made, based on qualitative research,2 that we (clinicians) greatly influence patient values on account of the narratives we disseminate during our interactions with them.

A common question that often arises when discussing EBP is what constitutes evidence? Guyatt et al.3 offer the following definition: “Any empirical observation about the apparent relationship between events constitutes potential evidence.” This definition suggests that not all evidence ought to be considered equally. A discussion regarding hierarchy of evidence is outside the scope of this article and is well-described elsewhere.4

Because what can be considered evidence-based is often a rapidly evolving standard, evidence-based practitioners are encouraged to align their practice styles with good quality research evidence, affording them the ability to alter their stance on topics as the evidence changes, rather than anchoring their beliefs based on anecdotes and experience. Interestingly, this understanding comes from the wisdom developed through experience, which certainly has a role to play in evidence-based practice.

References:

- Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. A., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 312(7023), 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

- Setchell, J., Costa, N., Ferreira, M. et al. Individuals’ explanations for their persistent or recurrent low back pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 466 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1831-7

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-Based Medicine: Principles for Applying the Users’ Guides to Patient Care. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1290–1296. doi:10.1001/jama.284.10.1290

- McNair, P., & Lewis, G. (2012). Levels of evidence in medicine. International journal of sports physical therapy, 7(5), 474–481.

Joe Ghorayeb DC, MHA is a chiropractor with a special interest in physical rehabilitation, pain management and evidence-based medicine.

This article was originally published in the December 2020 edition of Canadian Chiropractor, and published online Jan 18th, 2021.

Print this page