What is Chiropractic? Proposing a future direction and understanding

By Joe Ghorayeb

Features OpinionWhen asked what chiropractic is, most – if not all – chiropractors will express the following sentiment to some degree: a health profession concerned with the assessment and management of conditions related to the spine, joints, nervous system and soft tissues.

The public often associates chiropractic with “back cracking,” mistakenly confusing a profession with a modality. The scope and practice of chiropractic continues to attract great public interest, rising to the forefront of media headlines, causing both members and observers alike to question whether the profession is deserving of continued self-regulation.[1]

In this op-ed, I will attempt to summarize the concepts of “profession” and “professionalism,” provide a concise history of the primary issue plaguing chiropractic and propose a future direction and understanding of what constitutes contemporary chiropractic.

What is a profession?

In the early days there were three so-called learned professions: divinity, law and medicine. Their origins arose from an obligation for individuals to administer the spiritual and corporal needs of a person and to legalize and regulate the disposal of their worldly goods.[2] At the time, that special claim lied less in the expertise of these individuals than in their dedication to something other than self-interest while providing their services.

Etymologically, “profession” means to proclaim something publicly. On this view, professionals make a promise and commitment to an ideal of a specific kind of activity and conduct.

In chiropractic, this act of profession occurs in two ways. One is the public profession upon graduation from chiropractic school; committing to the way the acquired knowledge and skills are to be used.

The second is in daily encounters with patients. Every time a clinician asks a patient “What can I do for you?” he or she is committing to two things: one is competence and the other is to use that competence in the best interests of the patient. This voluntary commitment engenders trust and incurs the moral obligations of that promise.

What is professionalism?

Several definitions of professionalism exist,[3-5] the salient features of which revolve around “a belief system about how best to organize and deliver health care, which calls on group members to jointly declare (“profess”) what the public and individual patients can expect regarding shared competency standards and ethical values, and to implement trustworthy means to ensure that all medical professionals live up to these promises.”[6]

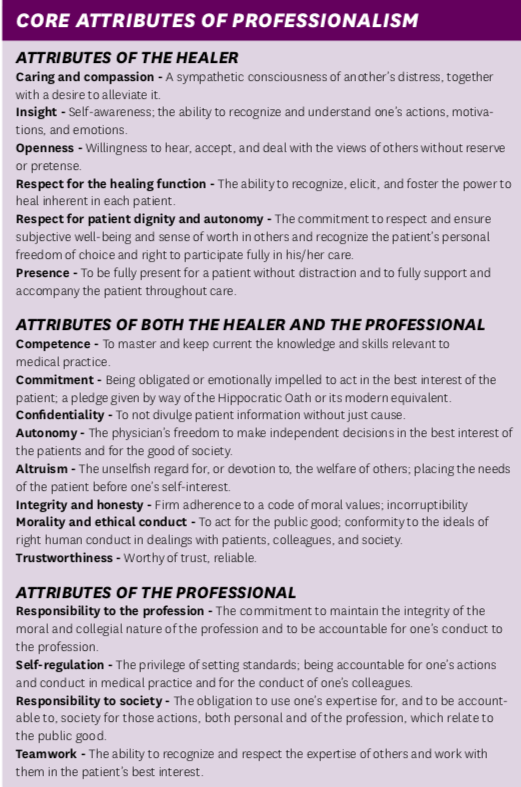

Prominent experts and researchers in the field offer core attributes of medical professionalism, which certainly apply to chiropractic:[7]

Committing to uphold these qualities reflects the unwritten yet implicit social contract that exists between society and chiropractic, where society relies on the profession to organize and deliver the health services it requires. In return, the chiropractic community is granted the privilege of self-regulation, influence and autonomy.

Ultimately, what has traditionally distinguished health care professionals from professionals in other fields is a strong sense of altruism.[8]

A History of Infighting

Unfortunately, a long-standing dichotomy exists within the chiropractic profession that continues to impede unified progress in the right direction.

On the one hand, chiropractors espousing the notion of vitalism make the argument that “living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element, or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things.”[9] This notion was effectively refuted in 1828 by Friedrich Wöhler, a German physician and chemist, who published a paper describing the formation of urea, known since 1773 to be a major component of mammalian urine, by combining cyanic acid and ammonium in vitro. In these experiments, the synthesis of an organic compound from two inorganic molecules was achieved for the first time. [10]

Unaware or uninformed of this established understanding, D.D. Palmer, the founder of chiropractic, coined the term “innate intelligence” to cast the idea that a vital force exists in the body and that human disease is the result of interference of the flow of this life force, by way of vertebral subluxations. [11] Thus, the straight or vitalistic chiropractor believes that the removal of subluxation by spinal adjustment, not to be confused with joint manipulation, is their sole responsibility in ensuring the unencumbered flow of innate. Proponents of this ideology opine that the delivery of an adjustment entails the specific application of force to the body with the intent and purpose of correcting vertebral subluxations, whereas joint manipulations are believed to be crude, non-specific forces haphazardly administered to the body.

On the other hand, chiropractors embracing science-based practice reject this antiquated dogma in favor of maintaining a keen responsibility to ensure that the treatments they administer are supported by high-quality evidence that meets scientific rigor: the strict application of the scientific method to ensure unbiased and well-controlled experimental design, methodology, analysis, interpretation and reporting of results.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that science-based chiropractors question the merit of the subluxation construct.

The universal definition of subluxation, adopted by the World Health Organization, describes an incomplete or partial dislocation of a joint. Whereas the esoteric definition, adopted by vitalistic chiropractors, calls for subluxation to be viewed as a process that portends “dis-ease,” rather than a static condition.[12] Mirtz et al.[13] applied Hill’s criteria of causation to examine the validity of the subluxation construct and concluded: “There is a significant lack of evidence to fulfill the basic criteria of causation. This lack of crucial supportive epidemiologic evidence prohibits the accurate promulgation of the chiropractic subluxation.” Thus, rendering this notion of subluxation to be a non-existent and inconsequential matter.

Nevertheless, if we were to assume that subluxation, in the esoteric sense, exists, one would hope that we possess appropriate methodologies of detecting such a lesion. A review of some commonly utilized tools and their significance is described below.

Static and motion palpation techniques are often utilized to identify malposition of a joint, whereas muscle palpation attempts to identify changes in soft tissue texture. As it happens, the reliability and validity of palpation, in general, is poor.[14-24]

Postural assessment is employed by some chiropractors as a means of predicting future episodes of pain and dysfunction or causally linking one’s pain with the presence of postural alterations. A review of the literature demonstrates that variation in “normal” postural alignment exists over a wide spectrum and does not mandate the need to make interventional decisions.[25-30]

Some practitioners with particular technique preferences that call for radiographic line analysis; measuring millimeter differences in alignment and posture, opt to identify deviations in spinal curvatures and offer the narrative that adjustments correct and maintain ideal spinal curves in order to prevent or reverse the degenerative processes typically associated with aging. Again, there is no evidence to substantiate this claim nor has this method of analysis been validated as a diagnostic tool. [31-33]

Notwithstanding the lack of evidence to detect the presence of subluxation, our ability to correct it via specific adjustments is poor. So poor, in fact, that we are generally off by one vertebral level from our intended target. [34] Moreover, while several theories regarding the mechanism of joint manipulation and other forms of manual therapy have been proposed [35-46], at this time we have yet to reach a conclusive mechanism of action for the modality that has become synonymous with chiropractic care.

Recalibrating our focus

Putting our philosophical differences aside, it is likely that all chiropractors agree that our role is to promote health, alleviate pain and improve quality of life.

This raises the question: What is “health”?

Huber et al. argue that health is characterized by “the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of physical, emotional, and social challenges.”[47]

Thus, it stands to reason that chiropractors ought to focus on enhancing human adaptability and resilience, in addition to promoting self-efficacy, while recognizing the role that biological, psychological, and social factors play in influencing the patient experience and the potential indications for administering specific treatments.

In light of this information, where do we go from here?

A call for order and progress

Moving forward, I envision chiropractors emerging as leaders at the intersection of health care and fitness. In order for this to occur, chiropractors, as a collective whole, would be better served to embrace the utilization of science-based interventions, namely exercise, as the primary mode of care.

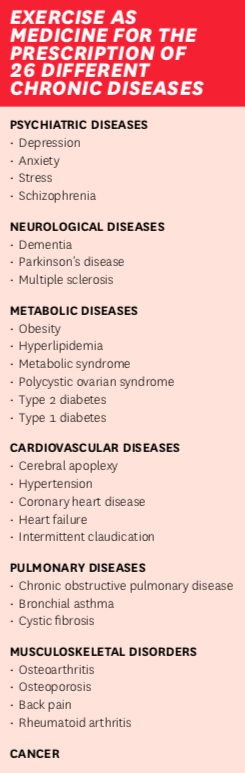

Exercise has been shown to confer many health benefits and is a cornerstone in disease and mortality risk reduction.[48-49] More importantly, there are no non-responders to exercise. [50] The same cannot be said for manual therapy.[51]

Just as a physician prescribes a specific dose and formulation of medicine to influence its effect within a therapeutic range, so too should a chiropractor prescribe, and monitor, a specific dose and formulation of exercise: detailing exercise type, intensity, frequency and duration with a specific goal in mind.

Exercise prescription does not mean to simply offer a list of exercises for patients to perform at the clinic, home or gym. It requires an understanding of the physiological adaptation to stress in order to achieve a favorable outcome through an individualized plan. Monitoring exercise load is necessary to observe positive adaptations, reduce the risk of injury and guide progression as work capacity increases. This mandates that the practitioner partner with their patients through the process of behaviour change.

Physicians face many obstacles when prescribing exercise to their patients. These include a scarcity of referral pathways, lack of time, not having adequate access to reference materials to guide them, and lacking confidence in the services they are referring to.[52] Chiropractors are uniquely positioned to lead the effort for change in this area because we are trained to prescribe and supervise exercise to address the needs of our patients.

Pedersen and Saltin provide evidence for the basis of prescribing exercise, in conjunction with medical care, in the treatment of 26 different diseases.[53] Expanding the reach of chiropractors interested in adopting this model of care.

What is contemporary chiropractic?

Contemporary chiropractic may be described as a physical medicine specialty that deals with health promotion and functional restoration. Chiropractors evaluate and treat individuals with disabilities and impairments that result from injury or disease by organizing and integrating a program of physical rehabilitation.

As professionals committed to science-based practice, chiropractors play a significant role in improving the health status of the communities they serve.

REFERENCES

1. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-calls-grow-for-outside-regulation-of-chiropractors/

2. Klass AA. What is a profession?. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1961;85(12):698-701.

3. http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e

4. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice—english-1215_pdf-51527435.pdf

5. ABIM Foundation, American Board of Internal Medicine; ACP-ASIM Foundation, American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243-246.

6. https://www.abms.org/media/84742/abms-definition-of-medical-professionalism.pdf

7. Cruess R, Cruess S, Steinert Y. Teaching Medical Professionalism. Leiden: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Collier R. Professionalism: What is it?. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(10):1129-1130.

9. https://mechanism.ucsd.edu/teaching/philbio/vitalism.htm

10. Am J Nephrol 1999;19:290–294.

11. J Can Chiropr Assoc 1998; 42(1).

12.https://www.spine-health.com/treatment/chiropractic/subluxation-and-chiropractic

13. Mirtz TA, Morgan L, Wyatt LH, Greene L. An epidemiological examination of the subluxation construct using Hill’s criteria of causation. Chiropr Osteopat. 2009;17:13. Published 2009 Dec 2. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-17-13.

14. J.-Y. Maigne et al. / Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 52 (2009) 41–48.

15. Page, Isabelle & Descarreaux, Martin & Stéphane, Sobczak. (2016). Development of a new palpation method using alternative landmarks For the determination of thoracic transverse processes: an in-vitro study. Manual Therapy. 27. 10.1016/j.math.2016.09.005.

16. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32:379-386.

17. Triano et al. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013, 21:36.

18. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2017; 61(2).

19. French, S. D., Green, S., & Forbes, A. (2000). Reliability of chiropractic methods commonly used to detect manipulable lesions in patients with chronic low-back pain. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 4, 231–238.

20. Walker, B.F., Koppenhaver, S.L., Stomski, N.J. and Hebert, J.J. (2015) Interrater reliability of motion palpation in the thoracic spine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015. pp. 1-6.

21. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2016; 60(1).

22. Lucas, N., Macaskill, P., Irwig, L., Moran,R., & Bogduk, N. (2009). Reliability of physical examination for diagnosis of myofascial trigger points: a systematic review of the literature. The Clinical journal of pain, 1, 80–89.

23. Hsieh, C. Y., Hong, C. Z., Adams, A. H., Platt, K. J., Danielson, C. D., Hoehler, F. K., & Tobis, J. S. (2000). Interexaminer reliability of the palpation of trigger points in the trunk and lower limb muscles. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 3, 258–264.

24. Myburgh, C., Larsen, A. H., & Hartvigsen, J. (2008). A systematic, critical review of manual palpation for identifying myofascial trigger points: evidence and clinical significance. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 6,1169–1176.

25. Okada, E., Matsumoto, M., Ichihara, D., Chiba, K., Toyama, Y., Fujiwara, H., Momoshima, S., Nishiwaki, Y., Hashimoto, T., Ogawa, J., Watanabe, M., & Takahata, T. (2009). Does the sagittal alignment of the cervical spine have an impact on disk degeneration? Minimum 10-year follow-up of asymptomatic volunteers. European spine journal: official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 11, 1644–1651.

26. O’Leary, S., Christensen, S. W., Verouhis, A., Pape, M., Nilsen, O., & McPhail, S. M. (2015). Agreement between physiotherapists rating scapular posture in multiple planes in patients with neck pain: Reliability study. Physiotherapy, 4,381–388.

27. Côté, P., van der Velde, G., Cassidy, J. D., Carroll, L. J., Hogg-Johnson, S., Holm, L. W., Carragee, E. J., Haldeman, S., Nordin, M., Hurwitz, E. L., Guzman, J., & Peloso, P. M. (2009). The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders.Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 2 Suppl, S70-86.

28. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;36(4):811-6.

29. Analysis of cervical spine alignment in currently asymptomatic individuals: prevalence of kyphotic posture and its relationship with other spinopelvic parameters. Kim, Seok Woo et al. The Spine Journal, Volume 18, Issue 5, 797 – 810.

30. SPINE Volume 40, Number 6, pp 392-398.

31. Weinert, D. J. (2005). Influence of axial rotation on chiropractic pelvic radiographic analysis. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 2,117–121.

32. Cakir, B., Richter, M., Käfer W., Wieser, M., Puhl, W., & Schmidt, R. (2006). Evaluation of lumbar spine motion with dynamic X-ray–a reliability analysis. Spine, 11,1258–1264.

33. Coleman, R. R., Cremata, E. J., Lopes, M. A., Suttles, R. A., & Fairbanks, V. R. (2014). Exploratory evaluation of the effect of axial rotation, focal film distance and measurement methods on the magnitude of projected lumbar retrolisthesis on plain film radiographs. Journal of chiropractic medicine, 4, 247–259.

34. Ross, J. K., Bereznick, D. E., & McGill, S. M. (2004). Determining cavitation location during lumbar and thoracic spinal manipulation: is spinal manipulation accurate and specific? Spine, 13, 1452–1457.

35. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Pickar, Joel G. The Spine Journal, Volume 2, Issue 5, 357 – 371.

36. The Mechanisms of Manual Therapy in the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Pain: A Comprehensive Model. Bialosky et al. Manual Therapy 2009 October;14(5): 531-538.

37. Hans Chaudhry, Robert Schleip, Zhiming Ji, Bruce Bukiet, Miriam Maney, Thomas Findley. Three-Dimensional Mathematical Model for Deformation of Human Fasciae in Manual Therapy. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2008;108(8):379–390.

38. Cramer GD, Cambron J, Cantu JA, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Zygapophyseal Joint Space Changes (Gapping) in Low Back Pain Patients following Spinal Manipulation and Side Posture Positioning: A Randomized Controlled Mechanisms Trial with Blinding. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2013;36(4):203-217.

39. Funabashi M, Nougarou F, Descarreaux M, Prasad N, Kawchuk GN. Spinal Tissue Loading Created by Different Methods of Spinal Manipulative Therapy Application. Spine. 2017;42(9):635-643.

40. Unraveling the Mechanisms of Manual Therapy: Modeling an Approach. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy201848:1,8-18.

41. The frictional properties at the thoracic skin-fascia interface: implications in spine manipulation. Bereznick DE, Kim Ross J, McGill SM. Clin Biomech 2002 May; 17(4):297-303.

42. G.N. Kawchuk, S.M. Perle / Manual Therapy 14 (2009) 480–483.

43. SPINE Volume 41, Number 2, pp 159–172.

44. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2016; 60(3).

45. Waters-Banker C, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Kitzman PH, Butterfield TA. Investigating the Mechanisms of Massage Efficacy: The Role of Mechanical Immunomodulation. Journal of Athletic Training. 2014;49(2):266-273. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.2.25.

46. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, George SZ, Robinson ME. Placebo response to manual therapy: something out of nothing? The Journal of Manual & ManipulativeTherapy. 2011;19(1):11-19. doi:10.1179/2042618610Y.0000000001.

47. BMJ 2011;343:d4163 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163

48. Compr Physiol. 2012 April ; 2(2): 1143–1211. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110025.

49. Gebel K, Ding D, Chey T, Stamatakis E, Brown WJ, Bauman AE. Effect of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity on All-Cause Mortality in Middle-aged and Older Australians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):970–977. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0541.

50. There Are No Nonresponders to Resistance-Type Training in Older Men and Women. Churchward-Venne, Tyler A. et al. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, Volume 16, Issue 5, 400-411.

51. Vavrek D, Haas M, Neradilek MB, Polissar N. Prediction of pain outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of dose-response of spinal manipulation for the care of chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:205. Published 2015 Aug 19. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0632-0.

52. Seth A. Exercise prescription: what does it mean for primary care?. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(618):12-3.

53. Pedersen B, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2015;25:1-72.

[THIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE JUNE 2019 ISSUE OF CANADIAN CHIROPRACTOR]

Joe Ghorayeb DC, MHA has been in clinical practice since 2003 with a special interest in physical rehabilitation.

Print this page