What’s in a name: Evidence-informed or evidence-based practice?

By Carla Ciraco, Dr. Peter Emary (DC), Dr. Charles Fischer (DC)

Features Photo: © cunaplus / Adobe Stock

Photo: © cunaplus / Adobe Stock There is a common misconception within chiropractic and other healthcare professions that evidence-based practice prioritizes research evidence while ignoring clinician experience and patient preference, when in fact it incorporates and emphasizes all three of these pillars equally.1,2 Historically, chiropractors have often relied on their clinical experiences and professional judgements to inform decisions on how to manage patients in clinical practice.3 As a collective, chiropractors have also been very good at valuing the patient’s perspective in clinical decision-making, as evidenced by consistently high patient satisfaction rates with chiropractic services.4-6 However, where chiropractors and other healthcare providers continue to fall short is with incorporating research evidence into routine day-to-day practice.3,7-10 In recent years, the term evidence-informed practice has been integrated within the vernacular of evidence-based medicine/evidence-based practice,11-13 and it seems to be a more palatable term to many clinicians as it de-emphasizes research evidence, particularly in instances when there may be a lack of scientific evidence to support a particular treatment approach. Although this may provide clinicians with a perception of added clinical flexibility, it can be detrimental to patient outcomes and ultimately the reputation of the healthcare profession, especially if new high-quality research evidence becomes available (e.g., Côté et al.14) and this is either dismissed or ignored.

The purpose of this commentary is to differentiate between evidence-based and evidence-informed terminology in relation to chiropractic education and clinical practice. In addition, we hope to stimulate future discussion and debate regarding the appropriate usage of these terms within the wider chiropractic and naturopathy professions.

Evidence-informed vs. evidence-based practice

As illustrated during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, there can be a danger to “informing” one’s clinical decisions and patient communications with evidence such as anecdote or case reports, or relying on experience at the expense of up-to-date, high-quality clinical research.15 One needs to look no further than the International Chiropractors Association (ICA) and their recent reports regarding chiropractic care and its purported benefits on immune function that were posted on the association’s public website shortly after the beginning of the global pandemic in March 2020.16,17 The claims in these reports were based on low-level evidence, and were swiftly criticized and debunked by international chiropractic researchers and students from across the profession.15,18

Despite the recognition and adoption of evidence-based practice and its principles among a growing number of healthcare professions in the last several decades, there has been an increase in the use of the term, evidence-informed practice, within the chiropractic profession in the past few years.11 We are unsure if this same shift has been occurring within the naturopathic profession? Some have felt that the “evidence-based” term is either too rigid, or, is not relevant to clinicians when there is a perceived (or real) lack of research evidence to help answer a particular clinical question. The debate between the use of evidence-based versus evidence-informed terminology has similarly been reported within the medical and nursing professions.12,13 Some argue that the “evidence-informed” term is more flexible allowing the clinician to emphasize their clinical expertise and the patient’s values or preferences, particularly when only low-level evidence supporting a certain treatment approach exists. The idea is that when higher-quality evidence becomes available, the clinician’s approach will be amended to align with this new information. However, simply finding what satisfies an individual patient – or, in some cases, the individual clinician – and subsequently modifying a treatment approach as research becomes available is not enough to justify a treatment’s efficacy. Likewise, the “looser” nature of the evidence-informed approach never answers the impending question of how much evidence is needed to support a treatment method, ultimately hindering the progress of healthcare research and clinical practice.

Evidence-based practice, as originally defined from its inception,1,2 is the combination of best available evidence, clinical experience, and patient values/preferences. As evidence-based clinicians, and in the management of an individual patient, chiropractors and naturopaths should not rely on one or two of these pillars alone; they should combine and prioritize all three. As such, all three pillars of evidence-based practice are equally weighted at all times. Likewise, adopting an evidence-based approach facilitates communication between clinicians and other healthcare professionals because of its extensive use in mainstream medicine.2 So, while the difference between the terms “evidence-informed” and “evidence-based” may appear trivial, discussions of this nature advance our respective professions toward mainstream legitimization in healthcare.

While both evidence-based and evidence-informed practice have their advantages and disadvantages, we recommend use of the term, evidence-based practice, within the chiropractic and naturopathy professions, over that of evidence-informed practice. Similar recommendations have also been made by others.11,13 For instance, Walker11 argues that evidence-informed terminology is weaker than evidence-based terminology, and the attempt to change the name of evidence-based practice to evidence-informed practice is a form of “soft resistance” to the principles and discipline of evidence-based practice by chiropractors and/or associations within the chiropractic profession internationally.

While evidence-informed practice takes into consideration patient preferences and clinician experience/expertise, evidence-based practice also makes use of higher-level evidence such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In line with such evidence, there is a growing body of research to support the use of multi-modal chiropractic care in the management of patients with spine-related pain disorders.19-22 For instance, most international clinical practice guidelines endorse common chiropractic therapies including spinal manipulation, exercises, education, and reassurance as first-line treatments for acute and chronic non-cancer back and neck pain.19-22 Therefore, the majority of what chiropractors do in clinical practice when treating these conditions is already deemed by the wider scientific community and the general public as evidence-based.

Our primary concern is that “evidence-informed” clinicians may tend to use anecdotal evidence that is based solely on clinical experience and case studies or reports. While these are valid forms of evidence, they are at the bottom of the research hierarchy23 (Figure 1) and may not hold true for all patients. So, while the goal of evidence-informed practice is to be more “flexible” and less mechanical than the more stringent evidence-based approach, it is also counterintuitive to assume that lower-level evidence that has not been controlled for or randomized (e.g., case studies) will be applicable to all patients. Thus, in their attempts to emphasize patient values and clinical expertise, proponents of the evidence-informed model risk going down a slippery slope that can severely jeopardize the legitimacy of the profession, not to mention patient outcomes.

Evidence-based vs. evidence-informed terminology

Daily patient-provider conversations in healthcare utilize the word “based” as a foundation for decision-making with regard to chiropractic, naturopathic, and/or medical care. This is also the case with shared patient-provider decision-making involving informed consent procedures. Some of the near endless examples of this include clinical conversations regarding treatment. For example: “Based on your current symptoms and laboratory values, I would recommend speaking with your general practitioner about reviewing or changing your medications…” or, “Based on what you are describing, and based on my clinical examination findings, we need to consider referring you for additional evaluation by a specialist for your condition.” In contrast, and from a grammatical standpoint, using the term “informed” personifies inanimate diagnostic procedures in a way that serves to disengage patients from their medical or allied health care. Therefore, the notion of “informing” treatment plans or developing “informed” treatments neglects the patient’s role in the clinical setting, which is in direct contrast to what advocates of the evidence-informed model seek to establish by replacing “based” terminology with “informed” terminology.

Moreover, the word “based” is often verbalized in communication between two or more parties when a decision is being made, even for non-healthcare related matters. If one looks to a court of law or any hearing or arbitration process, decisions or judgements are ‘based’ on evidence in the given setting/process, and when these decisions are communicated to all parties they are disseminated as:“Based on the evidence in front of me…” or, “Based on the evidence presented to this court…” In other words, the term “based” has become rooted in the current societal vernacular.

Evidence-based education

Semantics aside, we believe it is crucial that chiropractic and naturopathy students receive an evidence-based education early on in their studies so that they are both exposed to the best available evidence and also equipped with the tools needed to seek out the best quality research in practice. While the Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE) requires chiropractic institutions to include coursework on research methods, many schools only dedicate one 2- or 3-credit hour course to this branch of the curriculum.24

Moreover, an international study of chiropractic students reported that 95.6% of the respondents claimed to have access to medical/healthcare literature but 70.7% felt they needed more training to apply evidence-based principles in clinical practice.24 These data highlight a detachment between evidence-based pedagogy and clinical applicability, demonstrating that chiropractic students prioritize clinical relevance more than research quality. This tendency can prove to be problematic because it signifies that students who are not well-versed in evidence-based practice are less likely to practice it as clinicians and favour the seemingly more flexible evidence-informed approach that allows them to pick and choose evidence to confirm their own biases. Hence, the reality of producing “cafeteria clinicians” that pick and choose evidence as they see fit, is a concerning one for practitioners and educators alike. Therefore, in addition to early exposure to research-based courses, the quality and rigour of these courses must also be taken into consideration to ensure that students become future healthcare practitioners who understand and apply evidence-based principles in their clinical practice, and not merely participate in these courses for the sake of graduating. For example, chiropractic students at D’Youville College undertake a series of evidence-based practice courses as a core component of the academic program. These courses enable students to acquire skills in scholarly writing, literature searching, formulation of PICO (i.e., Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) questions, critical appraisal, and application of the literature to clinical case management.25 Students are also required to write and present evidence-based case reports to further enhance these skills.26

Take-home message

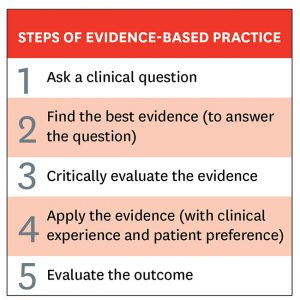

Any practicing clinician will have proficient clinical expertise and knowledge of their patients’ values, but few will know how to find the appropriate sources and critically appraise them for their validity – yet these are two of the key steps within the evidence-based practice approach (Figure 2). This lack of understanding and utilization of the basic underlying principles of evidence-based practice among chiropractic and other healthcare professionals is well supported in the published scientific literature. For example, numerous studies have shown that clinicians lack the necessary training and skills to competently search for, appraise, and apply high-quality research findings to the management of their patients.3,7-10

Furthermore, any patient can do a quick Google search and find case studies and personal experiences from other people, but patients do not know how to use databases, read the literature or appreciate the meticulous peer-review process that ultimately shapes clinical practice guidelines. Hence, what will differentiate a sound clinician will be his or her ability to provide patients with the best possible care, even if it seems “too rigid.” After all, doctor means “teacher” in Latin, and it is up to us as evidence-based clinicians to use our education and expertise to seek out the best information for our patients.

Conclusion

Although evidence-based practice is commonly misunderstood by students and clinicians within chiropractic and other healthcare professions, it is imperative that educational institutions, clinicians and professional associations disseminate the term “evidence-based” in favour of the more obscure “evidence-informed” term. As holistic healthcare professions advancing towards integration in mainstream and multidisciplinary healthcare systems, chiropractors and naturopaths need to be adequately trained to discern solid evidence from weaker forms of evidence to ensure that their respective professions maintain credibility. Similarly, as patient-centred healthcare professionals who have the privilege of using the title “doctor,” chiropractors and naturopaths need to be experts and teachers in the ongoing care of their patients. This will only improve the quality of our respective services, as well as the reputation of our respective professions. Ultimately, discussions pertaining to the use of language within the chiropractic and naturopathy professions, such as the one presented in this commentary, contribute to the maintenance of the professions’ integrity at a time when false medical information and pseudoscientific claims are reaching larger amounts of people in the public domain.

References

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71-72.

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Bussières AE, Zoubi FA, Stuber K, et al. Evidence-based practice, research utilization, and knowledge translation in chiropractic: A scoping review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):216.

- Gaumer G. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with chiropractic care: Survey and review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(6):455-462.

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: A systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115-130.

- Herman PM, Kommareddi M, Sorbero ME, et al. Characteristics of chiropractic patients being treated for chronic low back and neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(6):445-455.

- McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioners’ perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: A questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316(7128):361-365.

- Freeman AC, Sweeney K. Why general practitioners do not implement evidence: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2001;323(7321):1100-1102.

- Upton D, Upton P. Knowledge and use of evidence-based practice of GPs and hospital doctors. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):376-384.

- Schneider MJ, Evans R, Haas M, et al. US chiropractors’ attitudes, skills and use of evidence-based practice: A cross-sectional national survey. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23(1):16.

- Walker BF. The new chiropractic. Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24(1):26.

- Miles A, Loughlin M. Models in the balance: Evidence-based medicine versus evidence-informed individualized care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):531-536.

- Melnyk BM, Newhouse R. Evidence-based practice versus evidence-informed practice: A debate that could stall forward momentum in improving healthcare quality, safety, patient outcomes, and costs. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(6):347-349.

- Côté P, Hartvigsen J, Axén I, et al. The global summit on the efficacy and effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy for the prevention and treatment of non-musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Chiropr Man Therap. 2021; 29:8.

- Côté P, Bussières A, Cassidy JD, et al, and more than 140 signatories# call for an end to pseudoscientific claims on the effect of chiropractic care on immune function. A united statement of the global chiropractic research community against the pseudoscientific claim that chiropractic care boosts immunity. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):21.

- The International Chiropractors Association. Immune function and chiropractic: what does the evidence provide? Available at: http://www.chiropractic.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/ICA-Report-on-Immune-Function-and-Chiropractic-3-20-20.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- The International Chiropractors Association. Immune function and chiropractic: what does the evidence provide? – Revised. Available at: http://www.chiropractic.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Updated-Report-of-3-28-wtih-fixed-biblio.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- Plener J, Csiernik B, Bejarano G, Hjertstrand J, Goodall B. Chiropractic students call for action against unsubstantiated claims. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):26.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al, Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491.

- Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al; Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Clinical practice implications of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: From concepts and findings to recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S199-S213.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189(18):E659-E666.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al, Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: Evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368-2383.

- Haneline MT. Evidence-Based Chiropractic Practice. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2007.

- Banzai R, Derby DC, Long CR, Hondras MA. International web survey of chiropractic students about evidence-based practice: A pilot study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2011;19(1):6.

- Available at: http://www.dyc.edu/academics/schools-and-departments/health-professions/programs-and-degrees/chiropractic-dc.aspx. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- Bolton J. Evidence-based case reports. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(1):6-7.

Carla Ciraco is a 3rd-year chiropractic student at D’Youville College in Buffalo, NY. She graduated from the University of Toronto in 2018 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Kinesiology.

Dr. Charles Fischer is a chiropractor in private practice in Lancaster, NY. He also serves as an adjunct professor at D’Youville College in the Chiropractic Department.

Dr. Peter Emary is a chiropractor at a Community Health Centre in Cambridge, Ontario. He is a PhD candidate at McMaster University, and he also teaches in the Chiropractic Department at D’Youville College in Buffalo, New York.

Print this page